Tsodilo Hills (map)

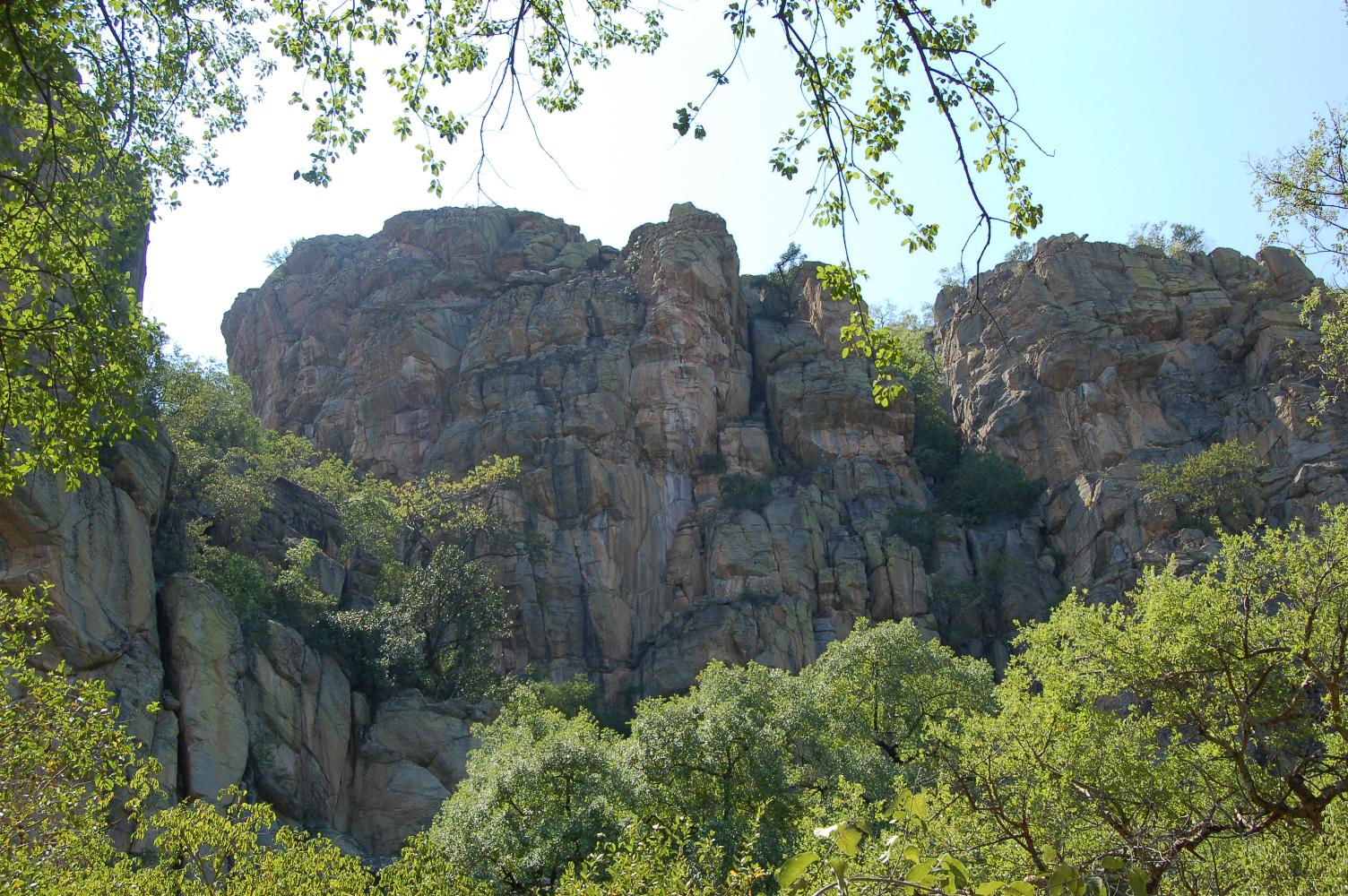

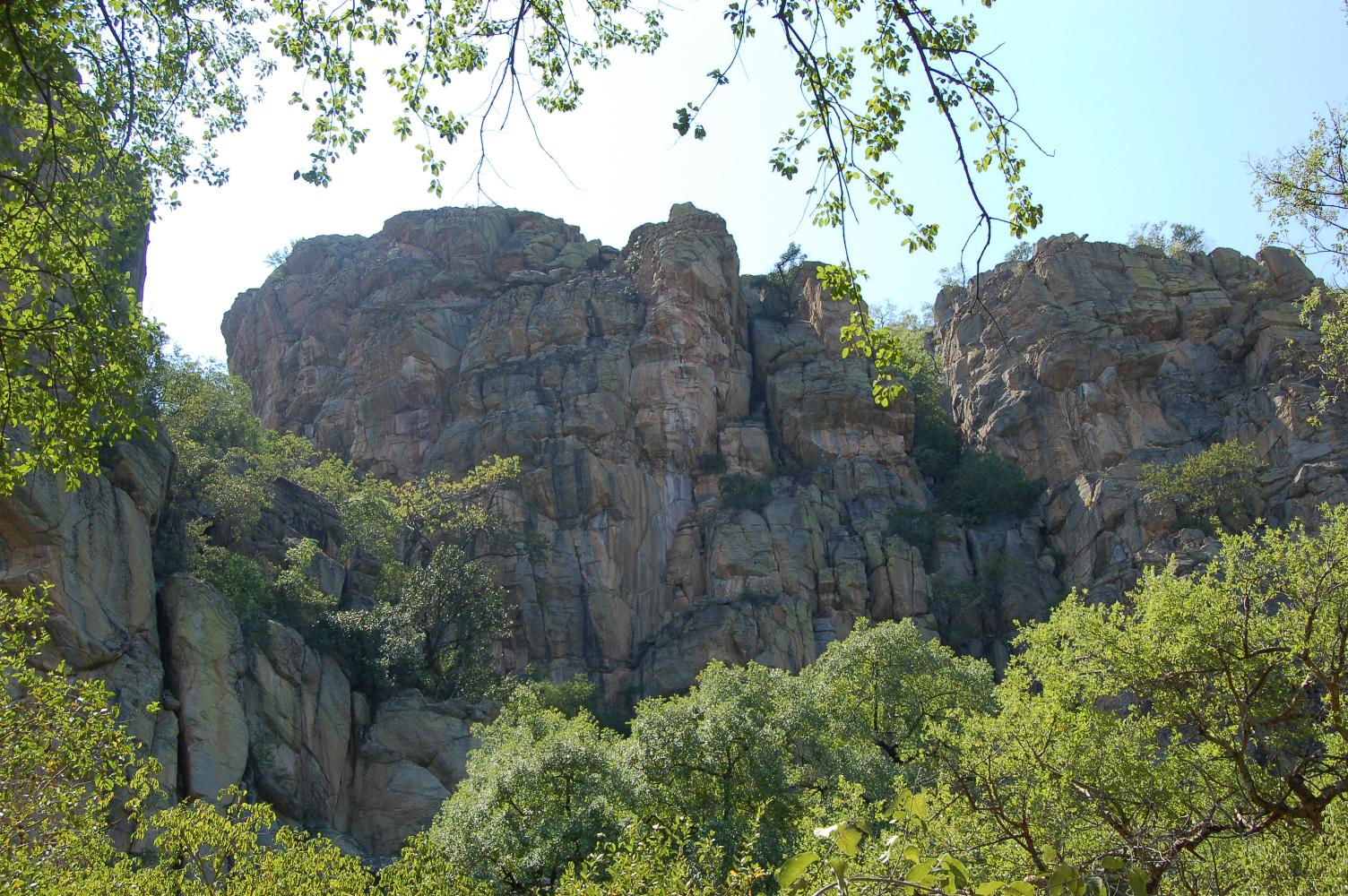

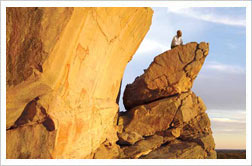

Rising abruptly, and dramatically, from the Kalahari scrub bush –

the rock face turning a copper colour in the dying sun – the magnetic power of

Tsodilo Hills both captivates and mystifies. There is an undeniable spiritualism

about the Hills that immediately strikes the visitor.

Tsodilo is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, located in north-western

Botswana. It gained its World Heritage Site listing in 2001 because of its

unique religious and spiritual significance to local peoples, as well as its

unique record of human settlement over many millennia. It contains over 4,500

rock paintings in an area of approximately 10 km² within the Kalahari Desert.

Geography

There are four chief hills. The highest is 1,400 metres AMSL and located at

18°46'18"S 21°45'15"E: the highest point in Botswana. The four hills are

commonly described as the "Male", this is the highest, the "Female", "Child" and

an unnamed knoll.

There is a managed campsite between the two largest hills, with showers and

toilets. It is near the most famous of the San paintings at the site, the

Laurens van der Post panel, after the South-African writer who first described

the paintings in his 1958 book 'The Lost World of the Kalahari'. The hills can

be reached via a good graded dirt road and are about 40 km from Shakawe. Also by

the campsite is a small museum. There is also an airstrip.

Cultural Significance

These hills are of great cultural and spiritual significance to the San peoples

of the Kalahari. They believe the hills are a resting place for the spirits of

the deceased and that these spirits will cause misfortune and bad luck if anyone

hunts or causes death near the hills. The San people believe these hills to be

the site of first Creation. Factually, the San people painted more than 4500

rock paintings against the magnificent stone faces of the Tsodilo Hills, making

it one of the most historically significant art sites in the world. The San did

most of the paintings, although there are a few by Bantu-speakers whose style

differs from that of the San. The exact age of the paintings is not known

although some are thought to be more than 20,000 years old. The hills contain

500 individual sites representing thousands of years of human habitation.

The hills are referred to by human attributes - male, female, child and the

male's first wife. The second tallest hill is referred to as the female. The San

people believe that the caves and caverns of this hill, the "Female" hill, are

the resting places of the deceased and various gods who rule the world from

here. The people of Hambukushu believe that their god, Nyambe, originally

lowered their tribe and livestock to earth on the female hill. Their supporting

evidence are hoof-prints clearly etched into a rock, high on the hill. (The

wordTsodilo is derived from the Hambukushu word 'sorile' which means sheer.) In

the northwest part of the female hill, some distance up from ground level is an

old mine that has filled with water. This water is considered to be holy water

and confers good luck on those that wash their faces with it. The most sacred

place is near the top of the "Male" hill, the biggest rock, where it is said

that the First Spirit knelt and prayed after creating the world. The San believe

that you may still see the impression of the First Spirits' knees in the rock.

The smallest hill is the 'child'. Finally, according to legend, the fourth hill

was the male hill's first wife, whom he left for a younger woman, and who now

prowls in the background.

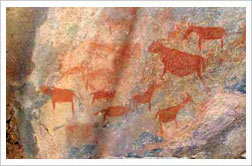

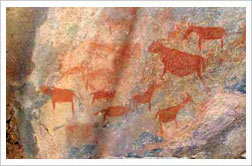

Rock Paintings

According to UNESCO, there are over 4500 rock art paintings in the Tsodilo

Hills. Most of the San rock paintings are found on the "Female" hill, the most

famous being the "Whale" painting, "Two Rhinos" and the "Lion" on the Eastern

face of the "Father". Some of the paintings have been dated to be as early as

24,000 years before present. There are numerous paintings, but relatively few on

the outlying hills. Indeed there are so many paintings in obscure places that it

is very unlikely they have all been discovered or documented.

There are recently installed trails and signs, but the paintings

are difficult to find without a knowledgeable guide. In fact, visitors are

obliged to take one of the local guides. This provides money to the local

economy and helps protect the site.

Alleged as site of earliest known ritual

In 2006 the site known as Rhino Cave became prominent in the media when Sheila

Coulson of the University of Oslo stated that 70,000-year-old artifacts and a

rock resembling a python's head representing the first known human rituals had

been discovered. She also backed her interpretation of the site as a place of

ritual based on other animals portrayed: "In the cave, we find only the San

people's three most important animals: the python, the elephant, and the

giraffe. Since then some of the archaeologists involved in the original

investigations of the site in 1995 and 1996 have challenged these

interpretations. They point out that the indentations (known by archaeologists

as cupules) described by Coulson do not necessarily all date to the same period

and that "many of the depressions are very fresh while others are covered by a

heavy patina." Other sites nearby (over 20) also have depressions and do not

represent animals. The Middle Stone Age radiocarbon and thermoluminescence

dating for this site does not support the 70,000 year figure, suggesting much

more recent dates.

Discussing the painting, the archaeologists say that the painting described as

an elephant is actually a rhino, that the red painting of a giraffe is no older

than 400 AD and that the white painting of the rhino is more recent, and that

experts in rock art believe the red and white paintings are by different groups.

They refer to Coulson's interpretation as a projection of modern beliefs on to

the past and call Coulson's interpretation a composite story that is "flatout

misleading". They respond to Coulson's statement that these are the only

paintings in the cave by saying that she has ignored red geometric paintings

found on the cave wall.

They also discuss the burned Middle Stone Age points, saying that there is

nothing unusual in using nonlocal materials. They dismiss the claim that no

ordinary tools were found at the site, noting that the many scrapers that are

found are ordinary tools and that there is evidence of tool making at the site.

Discussing the 'secret chamber', they point to the lack of evidence for San

shamans using chambers in caves or for this one to have been used in such a way.

Indeed for the people who live at the Hills – the San, the original inhabitants,

and the Hambukushu who have periodically occupied the hills for the past 200

years – Tsodilo is a sacred, mystical place where ancestral spirits dwell. In

earlier times, their ancestors performed religious rituals to ask for

assistance, and for rain. They also put paintings on the rock face; and their

meaning and symbolism remain a mystery even to today.

Exploring the three main Hills – Male, Female, and child – is a journey into

antiquity. Archaeological research – ongoing for the past 30 years – estimates

that Tsodilo has been inhabited for the past 100 000 years, making this one of

the world’s oldest historical sites. Pottery, iron, glass beads, shell beads,

carved bone and stone tools date back 90 000 years.

The Early iron Age Site at Tsodilo, called Divuyu, dates between 700- 900AD, and

reveals that Bantu people have been living at the hills for over 1000 years,

probably having come from central Africa. They were cattle farmers, settled on

the plateau, and traded copper jewellery from the Congo, seashells from the

Atlantic, and glass beads from Asia, probably in exchange for specularite and

furs. There was a great deal of interaction between different groups, and trade

networks were extensive.

Rock Paintings at Tsodilo Hills...Excavations also reveal over 20 mines that

extracted specularite – a glittery iron-oxide derivative that

was used in early

times as a cosmetic.

was used in early

times as a cosmetic.

Rock paintings are nearly everywhere – representing thousands of years of human

inhabitation, and are amongst the region’s finest, and most important. There are

approximately 4 000 in all, comprising red finger paintings and geometrics. It

is almost certain that most paintings were done by the San, and some were

painted by the pastoral Khoe who later settled in the area. The red paintings

were done mainly in the first millennium AD.

Two of the most famous images are the rhino polychromes and the Eland panel, the

latter situated on a soaring cliff that overlooks the African wilderness. Indeed

the inaccessibility of many of the paintings may be linked to their religious

significance.

The fact that Tsodilo is totally removed from all other rock art sites in

Southern Africa adds to its aura of magic. The nearest known site is 250

kilometres away. What’s more, the paintings at Tsodilo are generally unlike

others in the southern African region – in both style and incidence of certain

images. Many are isolated figures and over half depict wild and domestic

animals. In fact, there is a higher incidence of domestic animals than at other

sites in Southern Africa. Some are scenes, but few seem to tell a story. Many

are outlined schematic designs and geometrical patterns.

There are walking trails – the Rhino Trail, Lion Trail and cliff Trail, and

others; and it is recommended that you take a guide to walk the trails and see

the paintings. Both San and Hambukushu live near the hills, and guides from

their villages can be easily arranged.

There is a small museum at the entrance to the site; the main campsite at Museum

Headquarter has ablutions and water, while the three other smaller campsites

have no facilities. Because of its tremendous historical and cultural

importance, Tsodilo was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002.

With one of the highest concentrations of rock art in the world,

Tsodilo has been called the ''Louvre of the Desert''. Over 4,500 paintings are

preserved in an area of only 10 km2 of the Kalahari Desert. The archaeological

record of the area gives a chronological account of human activities and

environmental changes over at least 100,000 years. Local communities in this

hostile environment respect Tsodilo as a place of worship frequented by

ancestral spirits.

Brief synthesis

Located in north-west Botswana near the Namibian Border in Okavango

Sub-District, the Tsodilo Hills are a small area of massive quartzite rock

formations that rise from ancient sand dunes to the east and a dry fossil lake

bed to the west in the Kalahari Desert. The Hills have provided shelter and

other resources to people for over 100,000 years. It now retains a remarkable

record, in its archaeology, its rock art, and its continuing traditions, not

only of this use but also of the development of human culture and of a symbiotic

nature/human relationship over many thousands of years.

The archaeological record of the site gives a chronological account of human

activities and environmental changes over at least 100,000 years, although not

continuously.

Often large and imposing rock paintings exist in the shelters and caves, and

although not accurately dated appear to span from the Stone Age right through to

the 19th century. In addition, within the site sediments, there is considerable

information pertaining to the paleo-environment. This combination provides an

insight into early ways of human life, and how people interacted with their

environment both through time and space.

The local communities revere Tsodilo as a place of worship and as a home for

ancestral spirits. Its water holes and hills are revered as a sacred cultural

landscape, by the Hambukushu and San communities.

Criterion (i): For many thousands of years the rocky outcrops of Tsodilo in the

harsh landscape of the Kalahari Desert have been visited and settled by humans,

who have left rich traces of their presence in the form of outstanding rock art.

Criterion (iii): Tsodilo is a site that has witnessed visits and settlement by

successive human communities for many millennia.

Criterion (vi): The Tsodilo outcrops have immense symbolic and religious

significance for the human communities who continue to survive in this hostile

environment.

Integrity (2011)

The boundaries contain all the main sites. Three basic long-term facts have

contributed to Tsodilo’s outstanding state of preservation: its remoteness, its

low population density, and the high degree of resistance to erosion of its

quartzitic rock. The considerable archaeological evidence is generally well

preserved. All excavations are controlled in accordance with the national

legislation. Previous excavations have been properly backfilled and, in most

instances, leaving intact deposits and strata as a resource for future research.

The property attracts increasing visitor numbers, resulting in the need to

manage the threat of increased litter. Despite these increased visits, there

have been limited reports of vandalism and graffiti due to the compulsive guided

tour regulations put in place.

Authenticity (2011)

The authenticity of the rock art in terms of materials, techniques, setting and

workmanship is impeccable and, other than some impact caused by natural

deterioration and visitors, it remains as original as the time of its creation.

Conservation work has been limited to preventive strategies without altering the

art and its substrate.

The intangible values of the site continue to be practiced thereby

authenticating them as sacred and relevant to local communities. This approach

ensures their continued evolvement in line with traditional protection systems.

Protection and management requirements (2011)

The site owned by the Government is currently protected in terms of the

Monuments & Relics Act 2001, and by conditions of the Anthropological Research

Act 1967, National Parks Act 1967, and Tribal Act 1968.

Declared a National Monument in 1927, the responsibility for looking after

Tsodilo Hills rests with the Department of National Museum and Monuments in

collaboration with the Tsodilo Management Authority, an independent advisory

group comprising the Tsodilo Community Trust, community based organizations,

NGOs and selected critical government based Departments.

To ensure the conservation of all the site attributes, in 1997, a revised

Integrated Management Plan was developed and approved by stakeholders. An

Integrated management Plan detailing community initiatives was developed in 2007

and currently being implemented in the buffer area of the site. With the

assistance of the African World Heritage Fund, a Core Area Management Plan was

developed for the site in 2009.

The main objective of the previous and the current management plans is to ensure

the conservation of the values of the site. In addition to the existing site

office, and the Tsodilo Management Authority Trust, the Government has opened a

regional Monument office to directly oversee the implementation of the

management plan for the site.

Long Description

For many thousands of years the rocky outcrops of Tsodilo in the harsh landscape

of the Kalahari Desert have been visited and settled by humans, who have left

rich traces of their presence in the form of outstanding rock art. The outcrops

have immense symbolic and religious significance for the human communities who

continued to survive in this hostile environment.

Tsodilo is situated in the north-western corner of Botswana near the Namibian

Border. Its massive quartzite rock formations rise from ancient sand dunes to

the east and a dry fossil lake bed to the west. They are prominent isolated

residual small mountains surrounded by an extensive lowland erosion surface in a

hot dry region, known as inselbergs. Their height, shape and spatial

relationship have given rise to a distinctive name for each: Male, Female,

Child, Grandchild.

Caves and shelters are one of the main resources of the rock outcrop from the

human point of view. Where excavated, they show a long sequence of occupation

beginning in some cases as early as 100,000 years ago. They indicate repeated

use thereafter, the artefact densities appearing to reflect visits, perhaps

seasonal, by small mobile group of people. Divuyu and Nqoma are two excavated

settlements of particular significance in the 1st millennium AD. Divuyu lies in

a saddle at the top of Female; Nqoma is on plateaux below. A general pattern of

public housing and living space, flanked by communal middens and perhaps burial

areas, seemed to be the settlement plan, suggesting similarities with the

spatial patterning of villages of central Africa.

The rock-art paintings are executed in red ochre derived from hematite occurring

in the local rock. Much of the red art is naturalistic in subject and schematic

in style, characterized by a variety of geometric symbols, distinctive treatment

of the human figure, and exaggerated body proportions of many animals. In terms

of style and content the art has much in common with paintings of similar

antiquity in Zambia and Angola rather than neighbouring Namibia, Zimbabwe and

South Africa. A distinctive series of white paintings occurs at only twelve

sites: animals in white are rarer and include more domestic species than the

reds. Human figures are common, as are geometric designs.

The art is not well dated, although some of it could be more than 2,000 years

old. Pictures with cattle are regarded as 600-1200, following the introduction

of cattle to Tsodilo after the 6th century AD; geometric art is generally

regarded as about 1,000 years old. The latest paintings date to the 19th century

on oral evidence. Some white paintings appear to be riders on horses, unknown

until the 1850s.

Cup- and canoe-shaped hollows in rock, a common phenomenon throughout the

continent, are particularly numerous at Tsodilo. One group, interpreted as a

trail of animal footprints, is spread over several hundred metres and is one of

the largest rock pictures in the world. These hollows may have been made in the

late Stone Age, about 2,000 years ago.

The extent and intensity of mining activity on the mountains to recover ochre,

specularite and green stone, used for decorative purposes, is impressive. The

mines are clearly pre-colonial.

Source: UNESCO/CLT/WHC

Historical Description

Present evidence indicates the earliest occupants at Tsodilo probably in the

Middle Stone Age, perhaps around 100,000 years ago or earlier. A Late Stone Age

cultural presence is dated around 70,000 years ago. In general, repeated use

over an extensive period of time appears to reflect small mobile groups of

people camping briefly, perhaps on seasonal visits, for example when the fruit

of the mongongo tree, Ricinodendron rautanenii, ripens. Local quartz as well as

exotic stone were used for tool-making in both the Middle and Late Stone Ages.

The use of non-local raw material suggests that contact and some form of

exchange have existed at Tsodilo for tens of thousands of years. The Middle

Stone Age is marked by the appearance of large stone blades. Tsodilo is unique

in demonstrating an extensive record of freshwater fish exploitation in a now

arid landscape where rivers formerly flowed. Barbed bone points were probably

used to tip fish-spears; bone toolmaking at Tsodilo may well go back 40,000

years.

Fishbone and stone artefacts decrease in the Late Stone Age (c 30,000 BP). The

appearance of ostrich eggs in archaeological deposits around that time indicates

the development of a new strategy for acquiring a new resource for food and

artefact-making. In particular, a tradition of making beads of ostrich egg-shell

began then and continues today. Until as recently as c AD 600, the people of

Tsodilo lived entirely by hunting, fishing, and foraging for wild food.

By the 7th century AD, however, the pace of change in technology, subsistence,

and settlement organization increased as iron and copper metallurgy were

introduced. This phase is also marked by the introduction of cattle. Interaction

between Late Stone Age foragers and Early Iron Age agro-pastoralists occurred.

Settlement took the form of apparently unique social structures. Divuyu itself

is the richest site yet discovered in southern Africa for this period. Copper

and iron beads, bracelets, and other ornaments became common. All the metal was

imported - the copper probably from southern Zaire or north-eastern South

Africa, the iron perhaps from only 40km distant - and worked locally. Nqoma at

the end of the 1st millennium has the richest variety of metal jewellery of any

known contemporary site in southern Africa.

The same two sites in particular, Divuyu and Nqoma, have indicated domestic

herding and a settled lifestyle as early as the 7th-8th centuries AD from

evidence of middens and house foundations. Cultivated crops such as sorghum and

millet were added to the diet. Sheep and goats augmented the few domestic cattle

kept by earlier foraging communities. Pottery was produced for a range of

domestic purposes and personal adornment became common and often elaborate.

Mining for specularite was extensive in 800-1000, and continued into the 19th

century. The output was enormous, doubtless contributing to the amount of

jewellery and cattle owned by the Nqoma people. The rich elements of Tsodilo

Iron Age culture continued well into the 13th century when Nqoma declined,

possibly because of drought or war. No further durable exotic objects seem to

have entered the Tsodilo region until the effects of the European Atlantic trade

began to be felt in the 18th century. Tsodilo became part of the Portuguese

Congo-Angola trade axis.

Historically, the Tsodilo area was occupied by the N/hae, who left in the

mid-19th century. Its first appearance on a map was in 1857, as a result of

information collected by Livingstone during his explorations in 1849-56. In the

1850s the earliest known horsemen, Griqua ivory hunters, passed through the

region. The !Kung arrived in the area and made at least a few of the paintings,

possibly some of those showing horsemen. The rock art was first sketched and

brought to Western attention in 1907 by Siegfried Passarge, a German geologist.

The two, present-day local communities, Hambukushu and !Kung, arrived as

recently as c 1860. Nevertheless, they both have creation myths associated with

Tsodilo, and they both have strong traditional beliefs that involve respect for

Tsodilo as a place of worship and ancestral spirits. The spirituality of the

place has become best known to non-local people through the writings of Laurens

van der Post, notably The Lost World of the Kalahari (1958). Today, local

churches and traditional doctors travel to Tsodilo for prayers, meditation, and

medication. Most visitors arrive for religious reasons.

Coordinates: 18°46'18" S 21°45'15"E.

Accommodation

@ Drotsky's

Cabins

@ Guma Lagoon Camp

@ Lawdons Lodge

@ Nguma Island Lodge

@ Sepupa Swamp

Stop Rest Camp

@ Shakawe Lodge

@ Xaro Lodge

Contact:

E-mail:

was used in early

times as a cosmetic.

was used in early

times as a cosmetic.